The Wonders of Wild Foods

Note to readers: You can listen to this article by clicking on the voiceover recording above.

My feet push off crumbling rock and decaying leaves as I make my way up the mountain. Snowmelt trickles down the steep embankment, forming a crystal clear rivulet. I’m following an abandoned ox trail that was used to harvest bluestone on this mountain over a century ago. Since then, there’s been no human presence.

Further upstream, these vernal waters pause and spread out where the terrain levels out. Here, minerals wash down from the summit and settle in the moist and rocky soil where the wild leeks grow.

It’s April again, time for my yearly climb up the mountain behind my house to harvest these leeks – this precious wild food made from the mountain, of the mountain, by the mountain. Nothing human has tampered with them. Also called “ramps,” these sturdy plants have known neither box nor plastic bag. They’ve been carried in no truck, stored in no refrigerator, breathed no airborne carbons save the exhalations of porcupines, bobcats, and black bears. No pesticides or fertilizers have been applied to protect these plants or stimulate their growth. Instead, they form a symbiotic relationship with mycorrhizal arbuscular fungi, which dwell underground throughout this forest, microscopically growing into the leeks’ roots. The nutrient exchange that takes place (minerals from the fungi, plant sugars from the leeks) benefits both organisms. This fungus also enhances the plant's ability to uptake nutrients – especially phosphorus, mineral of light, essential for the production of energy in all living cells. Its name comes from the Greek word "phosphoros," meaning “light-bearer."

Arbuscular fungi also enrich soil and strengthen its physical structure. The mycelium emits and transports enzymatic and electrochemical signals in a fine and living network of communication that we are just beginning to understand. Both the wild plant and its invisible partner play an important role in this ecosystem. They’re inseparable from it, and their subtle array of constituents cannot be produced without it. Not just the elements of the earth but also the wind, rain, pollen, spores, frost, and dew that form upon its hearty leaves are all inculcated in this wildly nourishing plant.

And it is this wild nature, this intricate weaving of energy and matter, that we bring into ourselves when we eat wild food. To gather and consume it is to internalize both its nutrients and the context in which it lives. Wild food is the original, archetypal nourishment that sustained our ancestors for hundreds of thousands of years.

Wild plants are more complex than cultivated crops in their biochemical makeup. The soil where they grow is enriched not with packaged fertilizers, but with the owl pellet laced with the fur of a mouse . . . the breath of hemlocks in the cold night air . . . the bones of a deer buried in the forest floor. One can hardly imagine what is spun into these plants.

This is what I ponder as I make my way into a thick patch of leeks. Each plant has just two large leaves, with red stems and a single, bulbous root. I take off my backpack and grab my kitchen scissors, squatting down to get at the base of the plants. I snip off the broad leaves where they taper down into red stems, leaving the roots to generate new leaves next year. The leaves are superb sautéed in a quiche or simmered in soup. This patch is abundant enough to take some of the shiny white roots, too (most wild leek patches are not, and should not be depleted). I pry them up carefully with my digging tool. These will be added to my next batch of fermented vegetables.

Time passes. A raven lets loose its throaty call, then flaps away. I linger to gather just a few more leaves, and to breathe the forest air. All around me, similar patches of green bounty grow along both sides of the stream, extending as far as the eye can see. The springtime glory of Allium tricoccum is short, as these ephemeral plants soak up sunlight before the trees leaf out. As the foliage above broadens into a canopy, the leeks will turn yellow, and by late May finish flowering and die back into the earth. Their roots will be sustained throughout the year by the fungi, until the cycle of growth begins again next spring.

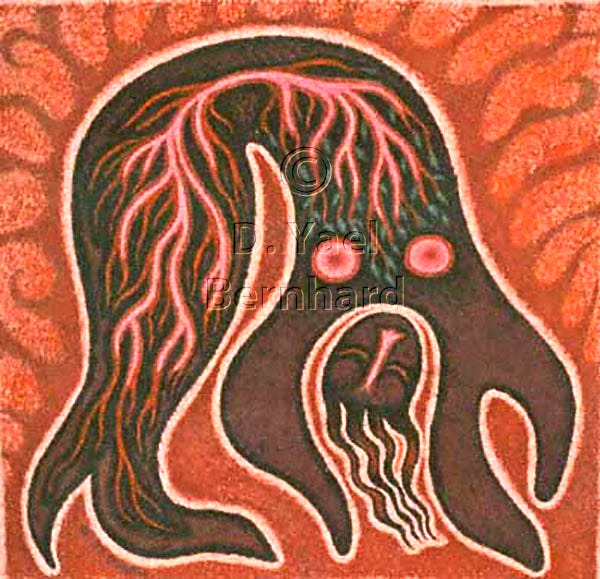

Foraging by nature aligns us with seasonal cycles, creating a relationship between where and when we gather and what we eat. Year after year, the ritual of foraging knits us to the earth, our true source of sustenance. This connection enriches our microbiome, tunes our endocrine system, soothes our nervous system, and mineralizes our tissues. Each wild plant, every mushroom is a manifestation of nature’s complexity. We don’t even know all the benefits we get from wild food. If “forest bathing” is beneficial merely by immersing ourselves in negative ions [which have positive effects], imagine, then, the deep nourishment offered by gathering and eating food from the forest. This sense of interconnection is known by hunters, fisherman, and foragers everywhere. There’s nothing quite like it. I tried to express this feeling in the painting shown above.

Wild plants and fungi are also hardier than their cultivated counterparts, for no nursery greenhouse coddles them, and no faucet delivers their water. They must endure exposure to the elements – wind and cold, drought and flood, fluctuations of moisture, salinity, acidity, temperature, and density of soil. Attacked by insects and parasitic fungi, nibbled on by rodents or gobbled by deer, wild plants and mushrooms muster their defenses in the form of potent antioxidants and immunological compounds. We, too, can reap the benefits of their efforts when we cook and eat them.

“Wild food carries beneficial bacteria, molds, and yeasts that:

1. Favorably alter the chemistry of the blood

2. Improve the mix of gut flora

3. Ease inflammation

4. Improve digestion

5. Support the heart and cardiovascular system

6. Stabilize mood and protect memory

7. Help us survive, even thrive, in polluted environments

8. Counter some of the adverse effects of drugs”

– Susun Weed, herbalist & author,

from “Wild Food Matters”

You don’t have to venture deep into the woods in order to find wild edibles. Many may be found in areas of human habitation, where wild plants thrive, often in abundance. Around your house may be the best place to find salad pickings or soup greens, from dandelion to chickweed, from violet leaves to purslane. If you do decide to forage in the forest, it’s important to bear in mind that these species may be rare or growing sparsely in a delicately-balanced environment. Please forage minimally and mindfully.

Whenever possible, I forage at home with bare feet. I want to tap into the earth’s electromagnetic field. I want to be part of that underground web. Damn the ticks and the torpedos, it feels important. When it comes to vital nourishment, I’m in with both feet. (And I do check myself for ticks afterward.)

Unless they’re picked by a dusty roadside, I don’t thoroughly wash wild plants. The wild leeks only get a quick rinse in the stream – I want the probiotic bacteria in those bits of soil clinging to their roots. I want the delicate pollen in a flower plucked for my salad, the wild yeast that lives on the surface of berries. These are friends to my microbiome, which thrives on the wild foods I feed it.

Springtime also brings mineral-rich clippings of young nettle leaves that grow along my driveway. They took root there of their own accord years ago. My guests have learned not to brush against these plants, for the sting of the tiny hairs on their leaves can be most unpleasant – or pleasantly stimulating, depending on your perspective. I wouldn’t dream of removing them, for this wild plant is a treasure chest of every mineral needed for human health, (except sodium). Nettles infusion – made from the dried leaves and stalk of the plant – is dark, rich, and satisfying, highly absorbable, excellent hot or cold (see my article Infuse Yourself With Liquid Nourishment for more on this subject). In addition to deep nourishment, Urtica dioca is also beneficial for the kidneys, lungs, and adrenals. Stinging nettles, which favors manmade embankments and roadside fields, has a sister in the forest, Wood Nettles (Laportea canadensis), with less elongated, more spade-shaped leaves. Wood Nettles is lovely to see along a wooded trail, but woe to the hiker with bare legs! This subspecies is not known to be as nourishing as Urtica – though it is also less studied.

Springtime foraging also includes the gathering of garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata), pungent and delicately-veined; coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), with yellow flowers that may be infused in honey to make a delicious cough syrup; and young horsetail plants (Equisetum arvense), their spiky plumes looking more like tiny pine seedlings, from which I make a vinegar extract to draw out their abundant minerals: calcium, potassium, magnesium, and most of all, silica for strengthening connective tissue such as cartilage, skin, hair, and nails.

Among spring-fruiting mushrooms are the beautiful pheasant-backs (Polyporus squamosus) that spread out like wings from the sides of trees. These attractive polypores are edible when young, but almost too beautiful to sacrifice. If it’s a wet spring, my garden might be graced with King Stropharia (Stropharia rugosoannulata), with their beautifully fringed red caps, growing wild from the wood chips in the shade of my rock wall. They grow and decay quickly, and must be cooked and eaten on the first day. The month of May also brings morels (Morchella esculenta), those rare mushrooms that are coveted for their unique flavor – but beware their poisonous lookalike, the False Morel (Gyromitra esculenta), known for its wrinkled, brain-like cap.

A word of caution about foraging mushrooms: always triple-identify a wild mushroom (and ideally, its lookalikes too) before you even consider eating it. This means positively identifying the mushroom in a field guide, on iNaturalist.com, or by consulting an experienced mycologist. Social media, crowd-sourced identification apps, and heresay from fellow foragers are not reliable. Edible mushrooms are a potent source of nutrition and medicine, and a delicious treasure to find in the wild. But equally potent are the poisonous species that populate the same habitats, many of which are mycorrhizal, forming symbiotic relationships with trees and enriching the soil – a gift to the forest – but not for humans. As a mushroom walk leader, I always tell participants never eat a mushroom unless you’re 100% certain you know what it is. Toxic reactions may range from digestive misery to death. Start by finding, observing, photographing and appreciating mushrooms, until you learn each species, one at a time, before eating them. With few exceptions, mushrooms should also never be eaten raw.

As spring yields to summer, new bounty arises: Wild strawberries (Fragaria vesca), small as raisins but packed with more flavor than a golf-ball sized store-bought version; lambs quarters (Chenopodium album), known by some as wild spinach; and yarrow (Achillea millefolium), with its finely-feathered leaves and sturdy clusters of flowers, renowned for their antiseptic properties. Yarrow flowers make an excellent tincture for healing wounds and brushing teeth. While picking them, I might also come across wild rose petals that melt on my tongue like perfumed fairy wings. And lovely chickweed (Stellaria media), with its tiny white flower like a little starburst, is ideal to nibble on raw or sprinkle on salads.

As summer Solstice approaches, Reishi mushrooms (Ganoderma tsugae) reach their ruby red maturity, looking more like seashells as they decompose dead hemlock wood. These majestic fungi perform alchemy on their substrate, contributing to nutrient cycling in the forest and producing powerful health-enhancing compounds that modulate immunity, blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol, sleep patterns, histamine response, and liver function. Reishi is not edible but makes a superb medicinal extract.

On a cool summer morning you’ll find me walking up the road to the watercress patch. Over the years, I’ve formed a relationship with this aquatic colony, so serene yet so spicy in taste. Mid-summer brings another wild array of edible plants: wood sorrel (Oxalis acetosella), tangy with vitamin C; violet leaves (Viola odorata), slippery and healing; purslane (Portulaca oleracea), rich in essential fatty acids; and my beloved red clover (Trifolium pratense), pink and robust, to be carefully dried to preserve its color, then infused for its nourishing phytoestrogens and alkalinizing properties.

One of my favorite rituals at this time of year is to walk out to my garden in my bare feet in the morning with a salad bowl or basket. I snip (and munch on) a few arugula leaves to add to my breakfast. As I walk back to the house, I meander a bit, looking for wild edible plants. If I want to keep them fresh for later in the day, I stand them in a glass of water on my kitchen counter. Sometimes I talk to the plants. They’re good listeners.

Wild mushrooms of mid-summer include chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius) that fruit along the buried roots of their mycorrhizal partners (usually conifer trees, depending on the subspecies). If you find chanterelles, be extra careful not to mix them up with toxic Jack-O-Lantern mushrooms (Omphalotus illudens). Boletes of all kinds (some edible, many not) also fruit at this time of year in a bold array of colors, a marvel to behold. More reclusive is the prized edible hedgehog mushroom (Hydnum repandum), with its cream-colored fringes beneath the cap – always a welcome find.

Late summer brings goldenrod (Solidago spp.), my plumed friends that fight colds through the winter as a vinegar extract; elderberries (Sambucus nigra), respiratory allies that fight viruses and yield dark purple anthocyanins in an alcohol-based tincture; and the final harvest of comfrey (Symphytum officinale), with its big bold leaves full of healing mucilage. Some say this is also the best time of year to pick dandelion leaves (Taraxacum officinale), as they have by now gathered plant sugars from a whole season of photosynthesis. Personally, I like them anytime, from spring to fall. Dandelion is a supreme ally to the liver, worth including in your diet, and maybe your dog’s too.

Wild fruits of late summer include blackberries, raspberries, and thimbleberries (Rubus parviflorus), picked along roadsides for their brain-boosting phytonutrients. A few more berries are ripe each day as my dog and I walk down the road (she gets some, too). Wild grapes and wild apples, dense and fibrous, may also be found – a reminder of what fruit was like for our ancestors. Wild mint, with its refreshing fragrance and square stems, may be steeped fresh or dried to make tea. Its cousin wild oregano, alas, is lovely to smell, but doesn’t hold its flavor when cooked. Better to add to salads.

Come early autumn, my shiitake-inoculated logs will fruit after a heavy rain – not exactly wild food, but ever so much more vigorous when grown outside. This is also the ideal time to look for rose hips and sumac berries (Rhus typhina), to steep into vitamin-C rich tea that makes for resilient capillaries, especially of the retina. I might find a cluster of shaggy mane mushrooms (Coprinus comatus) poking up from the earth like a collection of chess pieces; or a frilly mass of maitake (Grifola frondosa) growing from the base of a big old oak, drawing wisdom and nourishment from the great tree’s heartwood. And if I happen upon an edible Late Oyster mushroom (Panellus serotinus), I’ll consider it a lucky day. All are edible, once positively identified and thoroughly cooked.

As winter approaches, I’ll be outside snipping wild thyme from its bed of flat rocks that border my garden. The fragrance of the tiny, crushed leaves under my feet is heavenly. If I’m in the mood for exertion, I might take my digging fork down the road to the weedy patch where big-leafed burdock grows, to dig the stubborn, first-year roots of Artium lappa that grow straight down into the earth (burdock is biannual, and after flowering, the second-year roots are spent). The ultimate “yang” food for deep grounding, burdock is renowned for its nourishing and lubricating effects on the liver, stomach, kidneys, uterus, skin, and joints. I prefer infusion over cooking and eating the root. I’m sipping a cup of burdock root infusion as I type these words – so satisfying!

Certain fungi may be found anytime from spring to fall and even into winter: Turkey tail (Trametes versicolor) and Artist’s conk (Ganoderma applanatum), hardy polypores that are too tough to eat but may be simmered in broth for their immune-boosting polysaccharides; Chaga (Inonotus obliquus), a fungal conk that grows slowly on birch, prized for its antioxidants amd medicinal compounds; Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus), fruiting in bold and frilly clusters and tasting just like its name; and Witches Butter (Tremella mesenterica), little orange jelly-like clusters that enhance a soup or stew.

Like wild plants and fungi, wild meat is also spun from the forest. Wild turkey is infinitely richer than farm-raised poultry, and wild venison is way out of the ballpark of feedlot beef. These can hardly be considered the same foods, for the nutritional profile of wild or pasture-raised meat compared to factory-farmed meat is significantly different in terms of essential fats, proteins, and most of all, phytonutrients accrued from the animals’ diet of wild plants, nuts, seeds, berries, bark, moss, mushrooms, insects, and soil.

Life is not easy for wild animals, whether predator or prey. Seasons of scarcity and hardship forge great resilience. The long winter months build endurance. Everything gained shows up in their muscles, bones, and organs. Wild animal foods are incredibly sustaining, perhaps the greatest gift that money cannot buy. Here in the Catskill Mountains, these include whitetail deer, wild turkey, grouse, pheasant, black bear, and snowshoe hare.

Wild-caught fish – trout, salmon; small-bodied oily fish such as sardines, mackerel, and anchovies; shellfish such as oysters and mussels – are goldmines of essential fats. Whether fresh water or ocean dwellers, these aquatic animals are also manifestations of the complex ecosystem that sustains them. Mineral salts, aquatic plants and fungi, and microorganisms populate their homes and form their flesh.

Last but not least comes seaweed – slippery, slimy, mineral-rich, resilient and hardy seaweed. Together with krill (tiny microscopic animals eaten by sea mammals as large as whales), seaweed may be considered the foundation of ocean life. Though certain strains are sensitive to pollution, these wild plants of the sea play an important role in human health. Without them, we cannot get the iodine we need for healthy thyroid function, which governs numerous bodily functions, including metabolism, heart rate, body temperature, digestion, bone development, and even mood. Seaweed helps remove heavy metals from the body, and mitigates the effects of radiation. Some are high in iron; others contain unique compounds that hold potential for healing and sustaining the glycocalyx – the recently-discovered seaweed-like layer of microscopic, feathery tissue that lines every blood and lymph vessel in your body. A healthy glycocalyx is essential for cardiovascular health.

To properly sing the praises of seaweed, I’ll have to write a whole separate article. I’m still learning about these fascinating wild plants, here in my humble mountain home far from the coast. A trip to Maine is on my agenda for this summer.

These are some of the wild foods of the Northeast, some of which may also be found in other regions. Wherever you live, there are wild foods to be found, and there’s good reason to seek them out. We earn wild food with our perception, our legs, and our hands, spending time and effort rather than money. Thus we are doubly gifted, with not only nature’s nourishment but also observational skills, movement outside, and a profound sense of connection to the earth. To incorporate wild food into your diet is to incorporate yourself into nature. It all begins with a field guide and a basket.

To your good health –

Yael Bernhard

Certified Integrative Health & Nutrition Coach

Special thanks to herbalist Susun Weed for her input on this article.

Yael Bernhard is a writer, illustrator, book designer and fine art painter with a lifelong passion for nutrition and herbal medicine. She was certified by Duke University as an Integrative Health Coach in 2021 and by Cornell University in Nutrition & Healthy Living in 2022. For information about private health coaching or nutrition programs for schools, please respond directly to this newsletter, or email dyaelbernhard@protonmail.com. Visit her online gallery of illustration, fine art, and children’s books here.

Information in this newsletter is provided for educational – and inspirational – purposes only.

Are you interested in individual health coaching? Health coaching helps you reach your goals by making clear choices, taking realistic steps, and finding the resources and support you need. Respond directly to this post for more information.

Have you seen my other Substack, Image of the Week? Check it out here, and learn about my illustrations and fine art paintings, and the stories and creative process behind them.