Note to readers: You can listen to this article by clicking on the voiceover recording above.

As an integrative health coach, my training focused on two main areas: nutrition and lifestyle. Nutrition addresses dietary choices and habits, while lifestyle is all about behavior and the psychology of change. Most of my writing focuses mainly on nutrition. This article is more about the habits of mind that affect our nutritional choices, and offers a framework for finding guidance within yourself.

In my NBHWC (National Board of Health & Wellness Coaches) training program at Duke University, my classmates and I were taught to focus on challenges first, followed by outcomes and rewards. That’s why the title of this article is less bad, more good and not the other way around. We want to end on a positive note, even within a single sentence. People often have conflicting priorities, for example: I want to lose weight, but I don’t want to deprive myself of the foods I love. Both statements in this compound sentence are true. But changing the wording and order shifts this ambivalent statement to a process with a purpose: I find it difficult to give up foods that I love, but I know this will help me achieve my ideal body weight.

Many people find it easier to add good foods to their diet than to eliminate bad ones. But both are necessary, and getting rid of the bad ideally comes first. Why? Because there’s no substitute for removing the cause of a health problem. Let’s say you have leaky gut, which may lead to a whole cascade of inflammatory and autoimmune symptoms. You must first stop eating foods that damage the lining of your intestines – such as gluten, carrageenan, artificial sweeteners, alcohol, fried foods, and ultra-processed foods – before you attempt to repair your gut lining with healing foods. Bone broth, seaweed, slippery elm, yogurt, sauerkraut, and certain probiotics are all important helpers, but they cannot cancel out an onslaught of continuing damage. You must first remove the cause as much as possible, and then repair the damage.

What does “less bad” mean? It’s a question I often hear from friends, acquaintances, and health coaching clients. People want to know which foods they must really sacrifice, and which ones they can keep eating. Some of the most common questions concern sugar and starch:

“Ok, no more sugar. But is it okay if I keep eating maple syrup? Or honey? What about dates?”

“Can I still put oat milk in my cereal?”

“I don’t have to give up granola, do I?”

“I like to put raisins on my salad, is that okay?”

“I can just add one banana to my morning smoothie, right?”

These foods are all sugar in different forms, and all have a high glycemic index. And they all affect one of our primary metabolic markers: blood sugar. Blood sugar and insulin affect so many health issues, they’re likely to play a role in just about any chronic health condition, and to touch upon almost any health goal. That’s why these particular questions come up so frequently. People want to know: are these yummy foods we’ve been eating for decades sweet enough to matter? Can we eat them once in a while, or a little bit each day, or do we have to give them up entirely?

In answer to these questions, what most folks really want to hear is that they can keep eating these foods without consequence.

I try to let the questions answer themselves. “It depends on your health goals,” I say. “It’s not up to me – it’s up to your body.”

Often the person asks again, as if hoping for a different answer. “I’ve been putting bananas in my smoothies for years; do you really think one banana a day does too much harm?”

I’m not a sugar cop – but there is a force within your body that polices your metabolism. Homeostasis – a state of changing, responsive harmony – is constantly created and sustained by thousands of biochemical pathways, from enzymatic activity to hormonal secretions, from nerve impulses to nutrient-sensing pathways, from blood glucose levels to cellular fluid exchange. Encoded in these functions are the laws that govern your body. Your organs and systems enact these laws. Your pancreas silently judges the food you eat, and authorizes or withholds the release of insulin. Your insulin receptors traffic blood sugar. Your liver determines what to detoxify, how to process cholesterol; when to store sugar as fat and when to convert it back into sugar. Your blood pressure responds to precise mineral interactions. Within each cell, your mitochondria mobilize according to invisible instructions, generating energy to keep your body functioning. These are just a few examples of the internal goings-on that keep you alive.

None of these functions are consciously controlled. You can’t change the glycemic index of a banana (one of the highest of all fruits, depending on how ripe it is), or stop your morning cereal from causing insulin resistance. You can control how you think about the banana, what you choose to eat for breakfast, and how much stress you put on your pancreas to produce insulin. How important is it to prevent insulin resistance?

“Insulin resistance constitutes a six times greater risk of cardiovascular disease than elevated LDL cholesterol.” – Dr. Mark Hyman1

If you listen, your body provides the guidance you need about these dietary choices. From your body’s perspective, what would constitute “too much” harm? That’s an important question. Let’s suppose eating these sugar-rich foods on a regular basis would create a minor setback in lowering blood sugar and reversing diabetes or prediabetes. Would such a setback constitute “too much” harm? What about a moderately increased risk of heart attack or stroke? Or a flare-up of rheumatoid arthritis? A greater chance of developing Alzheimers disease, now known as “diabetes of the brain?” It’s up to you to decide. Personally, I would consider all the carbohydrates mentioned above too harmful, because they interfere with my long-term goals of constantly improving my metabolic and cognitive health. Why add heavy weights to your feet when trying to reach your destination? It will only slow you down, and delay the rewards and motivation that come with progress and results.

Imagine, for a moment, asking these questions about a houseplant. You want to take good care of it. You ask: “Can I uproot it just a little without causing harm?” “It’s okay to let some bugs eat its leaves, right?” “Can I just use sand instead of soil – that won’t make much difference, will it?” “Can I water it with beer?”

These questions seem silly. Common sense tells us a potted plant needs every advantage – healthy soil, a stable container, sufficient light, clean water, unpolluted air, and freedom from infestation – in order to thrive. Why sabotage your goal by avoiding the steps that will get you there?

Of course, people are more complex than houseplants, and humans have much more agency over their nutrition and health. But the principle is the same: less bad, more good is what moves you in the right direction.

When inflammation is localized in one area of the body, it’s easy to look for solutions that relate only to that endpoint. Acute inflammation from an injury or infection may temporarily warrant a narrow focus. But chronic inflammation is an underlying, ongoing condition that may manifest in numerous ways. If you have any signs of inflammation, be it worsening arthritis, increasing cataracts, persistent psoriasis or recurring headaches, reducing inflammation by means of diet and lifestyle is the safest way to mitigate your symptoms and prevent new symptoms from developing. Drugs may be faster, but always come with side effects, and rarely work well for chronic conditions. If removing the cause is what you want, then it’s in your best interest to eliminate inflammatory foods from your diet as much as possible, not as little as possible. And that, my friends, means careful consideration of your intake of sugar and sweets, industrial oils, factory-farmed meat, alcoholic beverages, and ultra-processed snacks, convenience foods, condiments, sauces, and cereals.

It works like this: The less refined carbohydrates, the lower your blood sugar. The lower your blood sugar, the less insulin your pancreas must produce. Less insulin means less insulin resistance by cellular receptors all over your body. Less insulin resistance means fewer free radicals. Fewer free radicals means less inflammation and cellular damage (see my article “It’s All About Insulin” for more on this subject.)

The longer and more you lower the level of inflammation in your body, the more results you will get: less joint pain, improved eyesight, better nerve sensation, fewer and milder headaches. The more good food you eat, the less you crave bad food. The less bad food you eat, the better your microbiome. The more you improve your microbiome, the better you absorb nutrients. The more you absorb nutrients, the steadier your energy. You can massage your whole metabolism into an upward spiral, into the shape you want, like a sculptor adding or subtracting clay as needed. Think long term as you make choices day by day, meal by meal. Keep your bigger goals in sight.

When making dietary changes, instead of thinking about how little change you can get away with, ask yourself how much change is needed to reach your goal? Does your body need a complete break from a particular food in order to achieve a reset? To change a biochemical pathway, this might be necessary.

“But I’m not allergic to gluten – can I still eat bread anyway?”

“Can’t I just put erythritol in my morning coffee?”

“I don’t know if there’s carrageenan in my almond milk or not. Does it really matter?”

“It’s okay if I have a glass of wine after dinner, right?”

The answer to all these questions is another question: “What will best serve your long-term health goals?”

It’s an ongoing process of eliminating inflammatory foods from your diet, and adding anti-inflammatory, nutrient-dense foods.

Let’s define these categories, and in doing so, we progress from less bad to more good:

Inflammatory foods include any mass-manufactured food made with refined sugar, refined grains (flour), industrial oils, or chemical additives. These include chips, crackers, cookies, candy, energy bars, cereal, bagels, most bread, instant powders, oil-roasted nuts, sauces, salad dressings, mixes, instant foods, substitute meat products, and confections like pop-tarts and pockets that can’t be made at home. Anything in a package with more than three or four recognizable ingredients is likely to cause inflammation within your digestive tract and beyond. Inflammation from free-radical damage in your bones contributes to osteoporosis. The same damage in your brain may lead to amyloid plaque build-up, or manifest as depression, anxiety, headaches, or brain fog. In your eyes, inflammation underlies macular degeneration and cataracts. In your auditory nerves it may trigger tinnitus or hearing loss. In your joints, arthritis may be the outcome. In your lungs, it could show up as asthma. If cancer is your concern, you have another reason to reduce inflammation and free radicals. Also known as reactive oxygen species or ROS, free radicals are unstable compounds that do cellular damage throughout the body, including the abnormal cell growth of cancer.

“Cancer cells maintain moderate levels of ROS to promote tumorigenesis, metastasis, and drug resistance; indeed, once the cytotoxicity threshold is exceeded, ROS trigger oxidative damage, ultimately leading to cell death. Based on this, mitochondrial metabolic functions and ROS generation are considered attractive targets of . . . natural anticancer compounds.”2

These natural anticancer compounds are found in anti-inflammatory foods. Anti-inflammatory foods are rich in antioxidants that fight or neutralize free radical damage: whole, low-glycemic fruits such as berries, apples, clementines, and pears; non-starchy vegetables; dark leafy greens; wild edible plants and roots; whole nuts and seeds; herbs and spices; wild-caught fish; mushrooms; and fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, miso, sourdough bread, kombucha, and sauerkraut. See my article “Activate Your Antioxidants” for more on this subject. Find lists of non-starchy vegetables online.

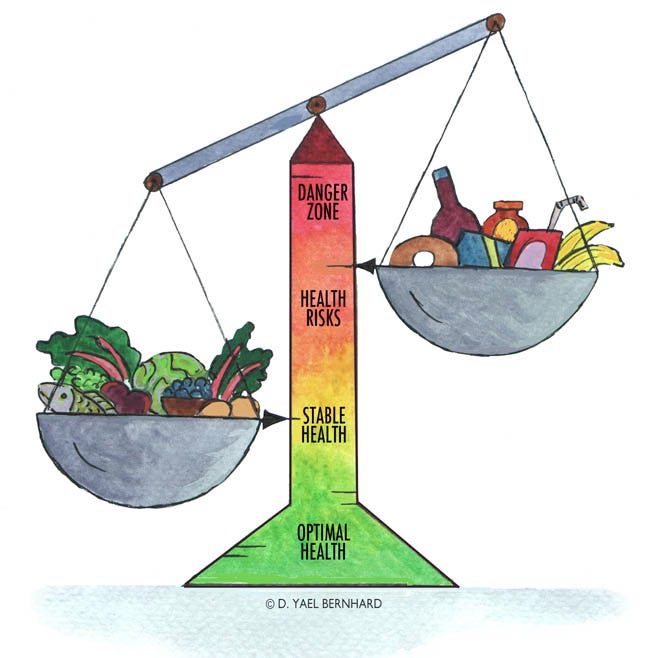

Nutrient-dense foods are generally rich in protein, fat, and/or fiber. As shown in the illustration above, they are bulkier and heavier than unhealthy or ultra-processed foods. Think of how little a bag of potato chips weighs compared to a baked potato; or the size of a fresh salad compared to a tablespoon of green powder supplement. Compact, light-weight foods may be more portable and convenient, but they’re less satisfying, contain less fiber, and have far less nutritional value. Processed foods may be completely lacking in antioxidants, which are often sensitive to heat or dehydration – or worse, transformed into free radicals in the preservation or packaging process.

Over time, by eating less bad and more good food, you may effect a sea change in your metabolism. This is the power of small, incremental steps to change the arc of your health. The process gains its own momentum with time. Just as someone who loses five pounds is encouraged to lose ten more, once you begin to feel relief from your chronic symptoms, your motivation will naturally increase.

The best way to speed up your progress is to do more, not less, to head in the direction of your health goals. Just as a sculptor must start a work of art with large chunks of clay, you may need to start with bigger changes. Like that beautiful houseplant you want to help flower, why not give your body every advantage?

The power to change your health begins by identifying your objectives and evaluating the necessary steps to achieve it. It could be a certain weight, better sleep quality, or a changed biomarker. Like that slip of wet clay waiting to create the shape you imagine, it’s all in your hands. Ask not what your body can tolerate, but what you can do for your body. Instead of looking for exceptions to minimize change, look for ways to maximize results. Keep subtracting the bad and adding the good, and you’ll be heading in the right direction. The cleaner your diet, the more rewards will keep rolling in. You’re the sculptor of your own future health.

To your good health –

Yael Bernhard

Certified Integrative Health & Nutrition Coach

Yael Bernhard is a writer, illustrator, book designer and fine art painter with a lifelong passion for nutrition and herbal medicine. She was certified by Duke University as an Integrative Health Coach in 2021 and by Cornell University in Nutrition & Healthy Living in 2022. For information about private health coaching or nutrition programs for schools, please respond directly to this newsletter, or email dyaelbernhard@protonmail.com. Visit her online gallery of illustration, fine art, and children’s books here.

Information in this newsletter is provided for educational – and inspirational – purposes only.

Are you interested in individual health coaching? Health coaching helps you reach your goals by making clear choices, taking realistic steps, and finding the resources and support you need. Respond directly to this post for more information.

Have you seen my other Substack, Image of the Week? Check it out here, and learn about my illustrations and fine art paintings, and the stories and creative process behind them.

Apple podcast: /us/podcast/rethinking-cholesterol-keto-and-cardiovascular-risk/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39857449/