Mycelium As Metaphor

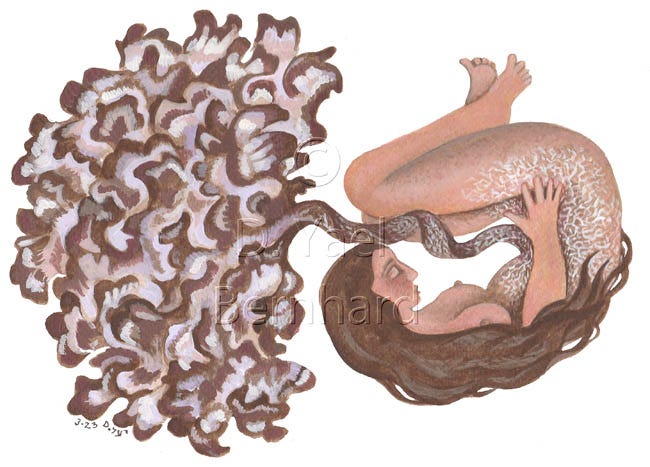

“Maitake Mother” illustration © Yael Bernhard

Here in the Catskill Mountains of upstate New York, foraging season is upon us. Last month I was out in the woods digging wild leeks. Friends sent photos of morel mushrooms they had found. Wild nettles are ready to harvest, just before flowering – a gold mine of bioavailable minerals that make up my daily morning brew. With sufficient rain, many more species of plants and fungi will follow.

In addition to being an illustrator, writer, and health coach, I also work for Catskill Fungi making medicinal mushroom extracts. I love this work, and the extracts that are part of my medicine cabinet, along with herbal extracts, oils, teas, and infusions. I also forage and eat wild mushrooms, and do my best to learn the Latin names of the thousands of fungal species that fruit in the fields and forests where I live. It’s a fascinating world, and there’s always more to learn.

All of this was on my mind as I wrote my last article, “The World Within You,” focusing on the interconnection between our bodies and nature. Yet there’s an invisible player that deserves further attention, for it knits the whole web of life together. It’s the mycelia of mushrooms – the underground body of fungi, and the very essence of biological connection.

When I first learned about mycelium, I thought of it as the roots of mushrooms. Plants have roots to draw water and nourishment from soil, I thought, and mushrooms also grow out of the earth, so they must have roots too. The dictionary defines mycelium as “the vegetative part of any fungus.” That was enough to satisfy my curiosity, at the time.

Later I learned that mycelium is actually what enables plants to draw nutrients from soil, by breaking down minerals with exogenous enzymes and translocating them into roots. Mycelium creates a cellular bridge that keeps plants alive. In return, the plants share up to 30% of the sugars they produce with the fungi, which cannot photosynthesize. This mycorrhizal, symbiotic relationship occurs in 95% of plants and trees worldwide, and makes it possible for them to live on land. Mycelium also creates soil itself, both by breaking it down and binding it together with its fine mesh of filaments that may be thinner than a human hair. It interconnects the entire forest and breaks down dead wood.

Not only the role but also the structure of mycelium surpasses that of roots. Like a river delta, it branches out according to the lay of the land over vast expanses. Like a neural network, it sends signals through its hyphal tips to other hyphae. Like the vascular system of a placenta, mycelium draws nourishment from the substrate around it and delivers it into the living, growing mass of its own fruiting body – like a fungal fetus that spins its own flesh from the raw materials delivered through the umbilical cord of the mushroom’s stipe, or stem. Mycelium surrounds the finest rootlets of the biggest trees, and grows up inside the woody flesh of its photosynthesizing partners. Like branching ice crystals on glass or the veins in an iris flower, mycelium forms beautiful labyrinthine patterns. Like a colony of coral, it interweaves with its neighbors and constantly responds to its environment. Like finely crocheted lace, it anastomoses, connecting back to itself in addition to branching outward, building connection in every direction. Like a communication network, mycelium is nearly infinite in its reach, an underground relay station that enables trees to communicate with each other through electrolytes and electromagnetic impulses. Scientists are only just beginning to understand the fungal intelligence of mycelium, and the fundamental role it plays in supporting life on earth. At the same time, like the creeping textures of mold and rotting decay, mycelium is also a decomposer, breaking down life to feed life yet to come.

Mycelium is reflected in this myriad of metaphors because it’s the very stuff of life itself. It’s a cellular superhighway of information, exchanging trillions of messages. Every square inch of soil is packed with a mile of mycelium. Without it, there would be no lichen to break down rocks, no plants outside the sea, no forests, and no insects, birds, or animals of the forest. Without mycelium, rotting logs would never become the fertile loam that incubates new seedlings. The entire land-based food chain depends on mycelium in order to exist – and so do we.

Mycelium is alive 365 days a year, pressure and chemical sensitive, responsive to stimuli and ever seeking to explore, connect, transmit, and receive. Like art and science, it becomes more intricate as it grows, branching out into finer and more specialized forms of expression. As creative processes in both nature and human nature progress from coarse to fine, mycelium embodies this progression. Thus it creates connection not only within the environment but also between the environment and our bodies – and within the imagination.

Somehow I managed to dwell on earth for more than half a century before I even knew of mycelium's existence. Now it’s nearly a household word, as people are becoming more aware of the silent mesh that undergirds life in the rhizosphere, and with it, our entire ecosystem. (You can find more facts about mycelium here and watch the documentary “Fantastic Fungi” here.) We would do well to use permaculture farming practices, such as no-till planting techniques, that encourage and preserve the life of mycelia.

The mushroom shown in this illustration is Maitake (Grifola frondosa), one of my favorite fungi because it’s both culinary and medicinal. At Catskill Fungi, we make a triple extraction of Maitake that draws out its beneficial polysaccharides, beta glucans, terpenes, antioxidants, and more. Maitake is known to support cellular health and immunity, to balance hormones, improve insulin sensitivity, lower cholesterol, inhibit the growth of hepatitis and cancer (especially hormonally-driven types), reduce hypertension, and even heal acne.1 Maitake is a Japanese name, as Japan is where most of the clinical research on this amazing medicinal mushroom has been conducted.2

Equally wonderful as a culinary mushroom, cultivated Maitake may be found in the produce section of some supermarkets, or if you’re lucky, you might find it growing at the base of a mature oak in the fall. The wild mushroom is far bigger and hardier, having drawn nutrients from the forest soil and strengthened itself against the hardships of a changing and highly competitive ecosystem. Tear the petals of this frilly mushroom off, and you might find a salamander living in its moist folds. Place the petals in direct sunlight for several hours before you cook them, and their ergosterols will convert into vitamin D2. Maitake is delicious stir-fried or added to any stew.

I like to imagine this mushroom’s mycelium interweaving itself with the old grandfather tree with whom it’s partnered, exchanging nutrients and electrochemical news of the forest – and perhaps some form of wisdom yet to be understood by our human brains. It’s all going on patiently out in the forest right now as I type these words, and as you read them. All mushrooms – even common grocery store button mushrooms – are adaptogenic, anti-inflammatory, and immunosupportive. Personally, I want to integrate the gifts of mycelium into my own cellular networks as much as possible.

Though mycelium doesn’t actually grow into our flesh and bones, we breathe fungal spores from birth to death, and colonize fungal microbes in our oral and gut microbiomes throughout our lives. The more experience I gain foraging fungi and making medicinal mushroom extracts, the more I reimagine the web of life as a mycelial network. I think of those fine white threads as my friends, both familiar and unfathomable. Like the gossamer veil of stars in the Milky Way that is home to our planet, the hidden tapestry underfoot is a vast and silent mystery.

To your good health –

Yael Bernhard

Certified Integrative Health & Nutrition Coach

Yael Bernhard is a writer, illustrator, book designer and fine art painter with a lifelong passion for nutrition and herbal medicine. She was certified by Duke University as an Integrative Health Coach in 2021 and by Cornell University in Nutrition & Healthy Living in 2022. For information about private health coaching or nutrition programs for schools, please respond directly to this newsletter, or email dyaelbernhard@protonmail.com. Her art newsletter, “Image of the Week,” may be found here. Visit her online gallery of illustration, fine art, and children’s books here.

Information in this newsletter is provided for educational – and inspirational – purposes only.

Rogers, Robert: Fungal Pharmacy: The Complete Guide to Medicinal Mushrooms & Lichens of North America, North Atlantic Books, 2011; pp192-196.

Powell, Martin: Medicinal Mushrooms: A Clinical Guide, 2nd edition, Mycology Press, 2014; pp.66-67