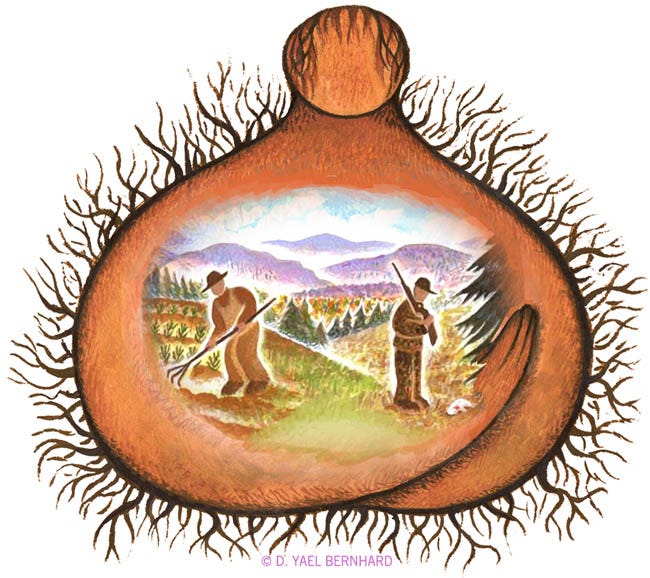

Illustration © D. Yael Bernhard

Note to readers: this article has been slightly edited since the voiceover (above) was recorded.

To eat meat or not to eat meat . . . that is the question, a fundamental one which has become increasingly controversial over the past few decades. No other dietary trend is so charged – or so confusing – as the decision to eat an exclusively plant-based diet, or not. Nutritional studies on the effects of both choices reveal seemingly conflicting – and sometimes outright misleading – information. Try researching the subject, and you’ll find yourself in a minefield of considerations, a shifting landscape of rapidly-changing discoveries. With good intentions, many people give up trying to make sense of it all, and make a decision to go vegan based on environmental, moral, or ethical grounds – which may resemble a religious vow more than a dietary choice – with little awareness of the effects on their own health. Agenda-driven influencers give bland reassurances that vegan diets are not only healthy, but superior – or the opposite. Where do we find steady ground to stand on?

Sources conflict on the number of vegans as well. According to one, only about 3% of Americans1 and 1% of the world population2 are vegan, yet these 88 million people have made themselves loudly heard. Books, organizations, podcasts, social media groups and cultural events have emerged as the voice of the vegan movement. The lines drawn in the sand have caused rifts in relationships and formed the basis of others. Food manufacturers have jumped on the bandwagon, bringing a whole new wave of mass-produced vegan foods to supermarket shelves – including vegan junk food.

Biologically, humans are omnivores. Our teeth, digestive system, and metabolism are designed to assimilate both plant and animal nutrients. But just as our reproductive capacities do not dictate that everyone must have children, not every omnivore must express their meat-eating genes. We have the capacity to subsist on foods of plant and animal origin. Does nature insist that we eat both?

No – but nor does nature dictate that we must be healthy. Since the birth of humankind, people have eaten flawed diets and thrived – for a time. Our ancestors died from injuries, infections, and acute illnesses, many of which were directly or indirectly linked to nutritional deficiencies. They lacked the technology and the luxury to pursue optimal health, and rarely survived a condition that today would cause a long decline. For example, two hundred years ago a diabetic lived only for months, and victims of stroke could not be rehabilitated.

We in the modern developed world enjoy a freedom from acute infectious illness that is unprecedented in human history. Unlike our ancestors, with our longer lifespans we must actively pursue good health. “Healthspan” wasn’t a concept our great grandparents thought about – but in today’s world, if we want to avoid a long decline, we must cultivate and preserve our long-term health. Chronic diseases come on slowly, emerging over time in the context of a person’s diet and lifestyle. Their seeds germinate in the soil of our daily habits: the food we eat, the air we breathe, the metabolic processes we engage in, the quality of our sleep, the toxins we’re exposed to, and more. These are all epigenetic influences on our overall health.

Without a doubt, the largest piece of this pie is nutrition. Nothing shapes our health more than the food we eat.

This is where conscious meat-eaters and vegans meet. We all want to pursue optimal nutrition and longevity.

Can we eat meat and be healthy? The short answer is: it depends. Can we survive without animal nutrients in our diet? Yes. Can we thrive and sustain good health without them? Maybe for a while.

Let’s explore these questions.

The following crucial nutrients are derived from plants, or (with the exception of fiber) from the meat, dairy, and eggs of pasture-raised or wild animals that graze on plants:

Vitamin C

Vitamin K1

Carotenoids

Sulfides (from all types of onions)

Polyphenols (of which there are thousands)

Flavonoids

Lignans

Sterols (the basis of many hormones)

Non-heme iron

Fiber (not exactly a "nutrient" but necessary for healthy digestion, and for feeding beneficial gut bacteria)

Without question, an optimal diet is largely plant-based, with vegetables ideally filling half your plate at any given meal. Here again, meat-eaters and vegans stand on common ground. We all need more plants in our diet – including vegetables and fruits, whole grains, nuts, seeds, fruit oils, spices, and herbs. Mushrooms also fall into this broad category, though they are not plants. Fiber only exists in plants and fungi, and is the driver of good digestion, regulating the rate of macronutrient breakdown and the secretion of insulin, which in turn affects our health in numerous ways. Fiber feeds good gut microbes that produce neurotransmitters, immune cells, and signaling molecules such as short-chain fatty acids. Gut bacteria also control neural networks through the gut-brain axis. Fiber is the first food I reach for at every meal.

The following nutrients are crucial for long-term human health, and may only be derived from animal sources:

Vitamin K2

Heme iron

Retinol (the usable form of Vitamin A)

Vitamin D3

Vitamin B12

DHA & EPA (omega-3 essential fatty acids)

These nutrients are worth closer consideration, as here is where we begin to wade into confusing waters.

• Vitamin K2 supports normal blood clotting and helps to usher calcium out of the vascular system and into the bones where it’s needed. Eggs, pasture-raised butter, cheese and poultry are some of the best sources. Japanese natto beans are one vegan source, but unless you live in Japan, this is difficult to eat on a regular basis.

• Heme iron is derived only from meat, most notably red meat such as beef, lamb, and pork. Heme iron is much more readily absorbed than non-heme iron from plants such as dark leafy greens and dried fruit. In order to be properly absorbed, plant-based sources of iron must be accompanied by an acidic food such as vinegar, citrus, or the amino acids in meat. Does too much heme iron put meat eaters at risk? In excess, yes – it has long been known that too much iron is dangerous, and possibly associated with cancer – a risk that has been greatly amplified by proponents of veganism, but is really nothing new. Moderation is key. Iron deficiency seems to be more of a problem in our culture, especially among menstruating women.

• Retinol may be easily derived directly from animal sources, or converted within the body from plant-based beta carotenes. In order to get enough from plants, be sure to eat dark leafy greens and orange and yellow fruits and vegetables on a regular basis. Vitamin A is fat soluble, therefore absorption is aided by consuming it with fat. Sufficient retinol is critical for the eyes, and for fighting off certain viruses such as measles. Supplementation may be problematic, as too much vitamin A is toxic.3Animal-derived foods are a higher source.

• Vitamin D3 may be derived from muscle and organ meat, dairy, eggs, sunlight on your skin, or mushrooms that have been exposed to sunlight prior to cooking. D3 plays many roles in the body, and is necessary for bone health and strong immunity, especially against viruses and respiratory ailments.

• Vitamin B12 is a critical nutrient for human health. Both vegans and vegetarians tend to be deficient, as eggs and dairy contain very little, and cooking may also destroy it. B vitamins are water soluble, and therefore cannot be stored. Contrary to common belief, nutritional yeast does not contain a usable form of B12 unless it’s artificially fortified with cyanocobalamin, the same active ingredient found in B12 supplements. Derived from a chemical process of microbial fermentation together with potassium cyanide and sodium nitrite, cyanocobalamin may be poorly absorbed, especially at higher doses and as we age. Worse still, artificial vitamins may even block receptors, impeding absorption from natural sources. If there is one nutrient that is imperative to get from meat, this is it. Two postage-stamp-sized squares of liver, the most nutrient-dense food on the planet, provide a daily dose.

• Essential fatty acids DHA and EPA are the building blocks of your brain and crucial for cardiovascular health, among numerous other functions. It is widely believed (and marketed) that omega-3 EFAs may be derived from flax, chia, and hemp seeds. But the body must first convert these into animal-based EFAs (DHA and EPA) in order to make them bioavailable. Pasture-raised grazing animals are able to do in their rumens, but in humans the process is slow and inadequate. Algae-based omega-3 supplements claim to do this for you, based on the idea that fish get their DHA and EPA from algae – but whether algae cultivated in vats provides this vital nutrient in a form that is bioavailable to humans remains to be seen. I’m skeptical. We are not fish and we are not ruminants. We are omnivores. This question is still evolving.

The following nutrients are abundant in animal foods, and may be derived only in small quantities or trace amounts from plants:

Creatine

Taurine

Carnitine

Glycine

Leucine

Zinc

Choline

C15 (essential fatty acid)

Again, let’s clarify the roles of these nutrients:

• Creatine, an amino acid found in grass-fed beef and wild-caught or regeneratively-farmed fish, is an important nutrient for cognition. Creatine tends to decline with age. This underscores the importance of quality and source. Grain-fed, factory-farmed animals and fish cannot produce sufficient creatine.

• Taurine plays important roles in the body, helping to reduce cellular senescence (deterioration or loss of growth), protect against telomerase deficiency, suppress mitochondrial dysfunction, decrease DNA damage, reduce inflammation, lower LDL cholesterol, and even extend lifespan. Taurine also tends to diminish with age. It is abundant in almost all kinds of meat and seafood, with smaller amounts in dairy, and only trace amounts in seaweed. Human breast milk is especially rich in taurine, provided the mother is well-nourished, and plays a crucial role in determining her baby’s brain development and future health.

• Carnitine is necessary for heart health, cognition, and many other metabolic functions. Carnitine levels also diminish with age. The typical vegan diet is said to provide less than 1/6th of what animal proteins provide. Carnitine is poorly absorbed from supplements.4

• Glycine and proline are two amino acids that are necessary for building collagen. They are found in small amounts in plants and algae, but their synthesis must be switched on by the presence of other amino acids – leucine, isoleucine, and valine – which are found in adequate amounts only in animal-based foods. As the most abundant protein in the body, collagen plays critical structural and functional roles throughout the body, including bones, teeth, skin, hair, nails, tendons, ligaments, fascia, cartilage, eyes, blood vessels, clot formation, and scar tissue. Without sufficient collagen, structural integrity is impossible to form or maintain, especially in children, teens, athletes, and aging adults.

• Leucine is a critical amino acid for protein synthesis, and ideally should be present at every meal. We’ll look more closely at leucine in Part 2.

• Zinc is abundant in meat, poultry, and seafood. Legumes and whole grains contain zinc as well, but they also contain phytates that bind to the mineral, lowering its absorption.

• Choline, an essential nutrient that helps control memory, mood, and muscle coordination, may be found in limited quantities in grains, legumes, and vegetables. Animal sources such as liver, egg yolks, red meat, and fish are rich in choline. Insufficient choline may lead to fatty liver disease, neurological disorders, and cardiovascular disease. Excess choline may also lead to cardiovascular disease through the production of TMAO, but only in the context of an unhealthy diet and lifestyle. Buyer beware: protein drinks, shakes, and energy bars that contain carnitine or lecithin may raise TMAO. Whether from plant or animal-based foods, choline is converted to TMAO by gut bacteria. For both vegans and omnivores, the healthier your gut microbiome, the less TMAO.

• C15 is an essential fatty acid that has only recently been discovered. We’ll look more closely at EFAs and fat in general in Part 3.

Supplements that claim to provide nutrients that may be missing from the diet are widely available, and for both vegans and omnivores alike, this is a popular solution. But is it a good one? It means depending on a manufactured product that is mass distributed through corporate channels and under the scrutiny of government institutions of questionable integrity. Fraud is endemic in the supplement industry, and numerous products are offered in the wrong form or dosage. Labels are often deceptive. To depend on supplements as a long-term solution not only costs ongoing expense but also begs the question: to what degree are we willing to divorce ourselves from nature? In my belief, no nutrient should come exclusively from a supplement. Optimal nutrition is always derived from whole, real food, cooked or prepared at home and ideally sold without a barcode.

What about complete protein? As a critical macronutrient, protein is an important consideration in dietary choice. Beyond the individual amino acids mentioned above, how much protein is needed for human health, and how much can we derive from plant sources?

In Part 2 of this article, we’ll continue to explore the importance of protein in plant-based and omnivorous diets.

To your good health –

Yael Bernhard

Certified Integrative Health & Nutrition Coach

Yael Bernhard is a writer, illustrator, book designer and fine art painter with a lifelong passion for nutrition and herbal medicine. She was certified by Duke University as an Integrative Health Coach in 2021 and by Cornell University in Nutrition & Healthy Living in 2022. For information about private health coaching or nutrition programs for schools, please respond directly to this newsletter, or email dyaelbernhard@protonmail.com. Her art newsletter, “Image of the Week,” may be found here. Visit her online gallery of illustration, fine art, and children’s books here.

Information in this newsletter is provided for educational – and inspirational – purposes only.

https://www.cookunity.com/blog/what-percent-of-americans-are-vegan

https://worldanimalfoundation.org/advocate/how-many-vegans-are-in-the-world/

https://lettucevegout.com/vegan-nutrition/vitamin-a-beta-carotene/

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/265761#as-a-therapy