Your Best Friend: Fiber

Illustration © D. Yael Bernhard

When I read James Nestor’s book Breath, I didn’t expect to learn about nutrition. As a self-described “pulmonaut,” Nestor takes the reader on a deep dive into pulmonary health, breathing techniques, and the evolution of respiratory anatomy, including the lungs and nasal passages. This inquiry led Nestor to the catacombs of Paris, where he was able to examine human skulls that date back as far as 300 years. There he observed the transition from our large-jawed ancestors to our present-day small-jawed society. Our predecessors had wider mouths and ample sinus cavities, resulting in far fewer pulmonary problems, and no dental crowding. With little refined carbohydrates in their diet, they also had fewer dental problems. By contrast, millions of people today suffer from crowded and decaying teeth, occluded nasal passages, and frequent respiratory issues.

Nestor was exploring the time period when low-fiber foods first became common among the elite. This was no coincidence. Although white flour was invented thousands of years ago, it didn’t become widely available until the 19th century. Novel foods – such as white baguettes and the fluffy white cake to which queen Marie Antoinette referred in her infamous wrist-waving comment – required very little chewing. Less chewing resulted in weaker facial muscles, especially of the jaw, which became narrower over time, resulting in crowded and overlapping teeth. Weakened muscles, crooked teeth, and smaller mouths failed to adequately support the developing palate. The inferior palate in turn could not support superior sinus cavities, which according to Nestor are significantly smaller today. The many respiratory problems with which we are all familiar evolved from there.

All beginning with lack of fiber. Fiber, which constitutes the structure of plants and fungi – composed of cellulose and chitin respectively – is the root cause of health in so many ways – or lack thereof, setting the stage for illness and malfunctioning body systems.

Wow. I took a deep breath, and tried to absorb what I read. Is this why I needed braces as a teenager? My small jaw was apparently handed down to me by my European grandparents, who thought they were enjoying the good life by eating the new manufactured and refined foods that were quick to prepare, easy to chew, and rapidly digested.

But when it comes to digestion, easier, and certainly faster, is not better.

Fibrous roots were a major part of hunter-gatherer societies. Some of these roots were so tough, they had to be chewed literally for hours. As one of the few remaining such tribes, the Hadza people of East Africa are renowned for their extraordinary health spans, which extend almost as long as their lifespans, an average of 70+ years. They are also known to have possibly the healthiest gut microbiomes in the world, with up to 40% more species of bacteria – largely because of the whopping 100-150 grams of fiber they consume each day. These fibers consist mostly of a yam-like tuber which must be chewed for up to three minutes before swallowing – after being reduced to a “quid” or dense core that is spit out. Extensive chewing not only exercises the jaw muscles but strengthens the palate and fully engages the salivary glands, enabling them to make a greater contribution to digestion. In addition, the Hadza eat a wide variety of other fruits and vegetables that contribute multiple polyphenols and further diversify gut bacteria.1

How many of us spend hours each day chewing our food? How often do you eat a whole root, such as the Jerusalem artichoke or beet root pictured above? On the contrary, some of our most popular convenience foods are delivered in liquid form, including juice, soda, smoothies or whipped purées – with little or no fiber.

Together with protein and fat, carbohydrates are one of the three macronutrients. But curiously, carbohydrates as a nutrient are not essential for human health and survival, as our bodies can (and do) break down protein and fat into the glucose we need for cellular energy. We also need the phytonutrients in fruits, vegetables, nuts, grains, seeds, and mushrooms, all of which also contain varying amounts of carbs. And fiber – that is, the structure of carbohydrates – is definitely necessary, and thus is considered a macronutrient by many nutritionists. Stripped of their fiber, carbohydrate foods have far less nutritional value.

Let’s look at some of the vital roles fiber plays:

• Fiber feeds your microbiome. This gut-friendly substance comes from plants and fungi, and may be either soluble or insoluble. Soluble fiber dissolves in water, creating a viscous solution that nourishes the digestive tract. Examples of soluble fiber include split peas, broccoli, artichoke, avocado, oatmeal, seaweed, mushrooms, and berries. Insoluble fiber, though not digestible by us, provides nourishment for probiotic bacteria. Examples of insoluble fiber include cabbage, bran, onions, beans, brown rice, nuts, lentils, sesame seeds, and apple skins. Insoluble fiber is considered prebiotic, meaning your gut bacteria ferment and feed upon these foods. When you eat fiber, you’re not only feeding yourself but the millions of microbes that populate your gut, which in turn produce numerous benefits, including the production of postbiotics – short chain fatty acids that regulate your cellular DNA and play a direct role in preventing cancer, especially of the colon. Many lists of prebiotic foods are available online.

• Fiber regulates the speed of digestion, slowing it down so that it arrives in your intestines more gradually, which in turns reduces the amount of insulin that is released. As a signaling hormone, insulin is what turns on fat storage. When it circulates in excess, it breaks down into damaging free radicals, causing oxidative stress. The less insulin that is released at once, the lower your systemic inflammation and the less blood sugar is converted into triglycerides (see my article “It’s All About Insulin” for more on this subject). Thus, eating fiber helps to lower triglyceride cholesterol, reduce inflammation, and lessen weight gain – all major benefits for metabolic health. Less than 12% of Americans are metabolically healthy. Eating fiber takes you one step closer to joining that minority – and hopefully making it a majority again someday.

• Fiber lowers cholesterol by literally escorting it out of the body. Your liver produces bile from cholesterol, which is then delivered to the intestines by the gall bladder, where it emulsifies fats. Your intestines need healthy bulk – the bolus that moves through your digestive tract, which is made up fiber – in order to enable the muscular action of the colon to work properly and keep your bowels regular. This mass of food and enzymes also absorbs bile, which then passes out of the body together with cholesterol, carried along by insoluble fiber. Without sufficient fiber, cholesterol from bile is reabsorbed back into the bloodstream – not ideal. No wonder the risks of cardiovascular disease are highest among people with low fiber diets.2

• Fiber is the substance that holds the thousands of phytonutrients that are also vital for your health. The many colors of whole fruits and vegetables are made up of these plant-based polyphenols that support everything from eye health to nerve function to connective tissue. The importance of these compounds can hardly be overstated – but when separated from their natural matrix of fiber, as in fruit juice, or processed into powders, as in fiber supplements, they do not behave the same way in our bodies. This is especially true of “free fructose,” (fructose separated from its fiber) which uses up a great deal of intestinal energy to be absorbed, places an additional burden on the liver, and is stored as fat rather than burned as energy. (See my articles “Fructose: Friend or Foe?” and “Pursuing a Plant-Rich Diet” for more on these subjects.) Eat your fruits, don’t drink them!

• Fiber contributes to satiation, helping to keep the hormone lectin well-regulated, which signals the brain that your stomach is full; as well as adiponectin, which can only come from a happy gut.

• Fiber is necessary for normal intestinal walls. Low-fiber diets of sticky, glutinous white flour foods such as cereal, bread, cookies, and cake, especially in children, may cause the formation of diverticula, pocket-like protrusions in the intestinal walls, which may in turn become inflamed with food that is caught there, causing painful diverticulitis. To avert this problem, mainstream doctors may actually suggest a low-fiber diet in order to reduce pressure on the inflamed areas – but this only caters to the symptom and does not provide a solution. Fiber makes for healthy tissue to begin with, and infusions (water-based extracts) of mucilage-rich plants such as plantain leaves, marshmallow root, linden flowers, certain seaweeds, burdock root, and slippery elm bark help to strengthen and heal the lining of the gut. (See my article “Infuse Yourself With Liquid Nourishment” for more on this subject.)

• Chewing fibrous foods stimulates receptors on the tongue to produce nitric oxide, a signaling molecule that brings a cascade of benefits. Nitric oxide dilates blood vessels, including to the brain, lowering blood pressure and improving cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health. The longer you chew your food, the more nitric oxide is produced. Chewing also stimulates the production of amylase, the salivary enzyme that breaks down starch. This begins the digestion process in the proper order, and reduces the load on your pancreas. If you swallow your fiber without chewing, as in a smoothie or purée – or if the fiber has been removed completely or destroyed by extrusion (such as what enables cornmeal to be molded into corn chips) or other industrial processing methods, you miss out on this vital step.

Modern foods do much to alter fiber. When white flour was first invented, removing the nutritious but oily and perishable outer layer of the wheat kernel helped the flour last longer. It also removed most of the nutrients, resulting in nutritional deficiencies in people who depended on this staple grain – especially B-vitamins, which regulate hundreds of bodily functions, including neurotransmitters and gene expression. But even non-white, whole grain flours are still flour – that is, a fine powder, and a far cry from its original form. Think of it: what our teeth and jaws, salivary glands and tongues are meant to do has been done for us by a machine.

That doesn’t mean you should never eat flour, but consider the importance of making whole plants and whole grain fiber a regular part of your diet. Rice has more fiber, for example, than rice pasta. Wheat berries and sprouted wheat have more value than muffins. Whole oat groats are digested and metabolized differently than rolled oats, oat flour, and worst of all, oat beverages.

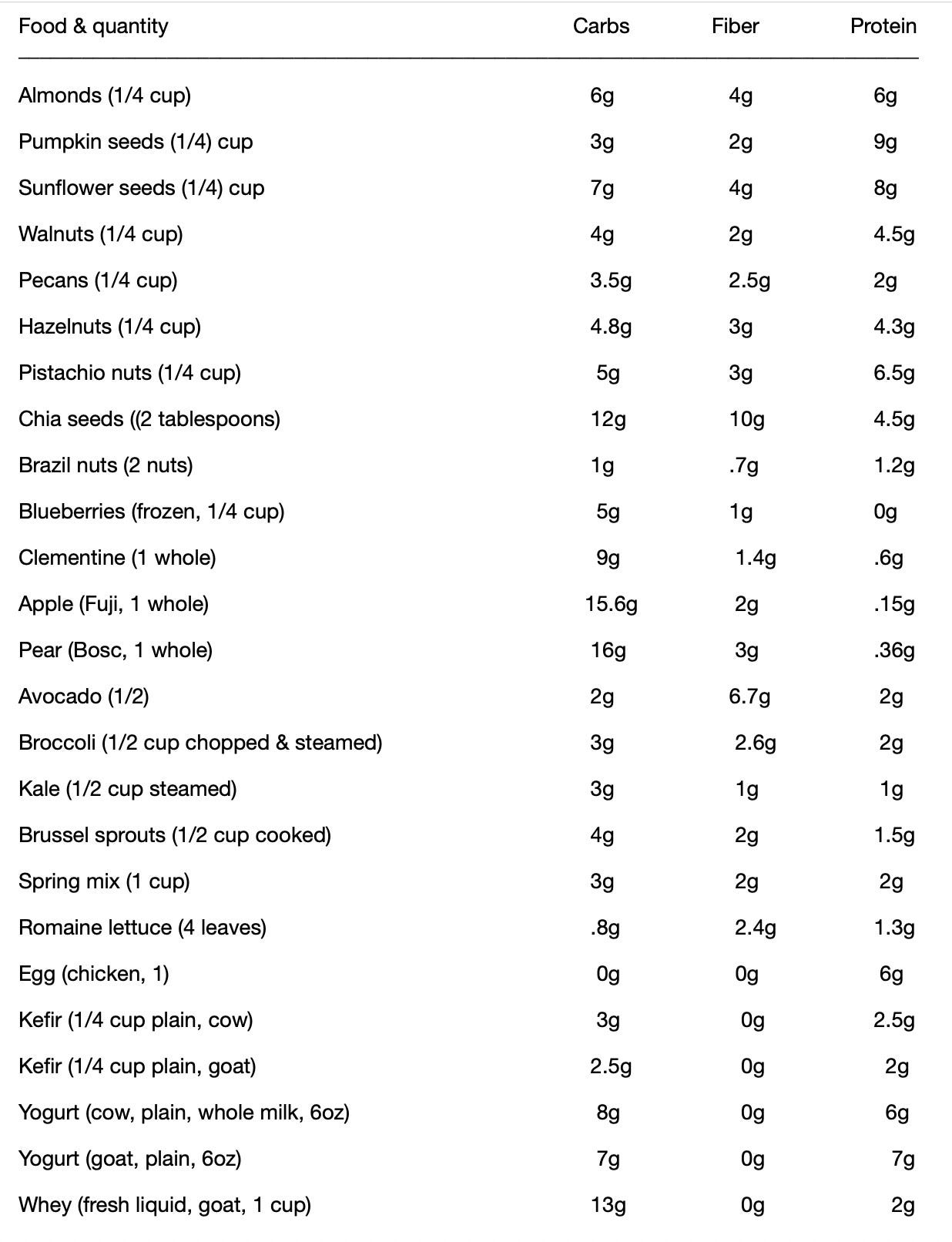

How much fiber is needed for optimal health? The average American eats less than the recommended daily amount of 30 grams per day – but the optimal level is closer to 50 grams. For me, keeping track of my dietary carbs, fiber, and protein for just three days was enlightening. It’s easy to simply search for the food and quantity you’re eating to find out how much it contains. Here’s my 3-day list:

Many of these foods repeated over the three days – but still, I wasn’t getting as much fiber as I thought. So I thought about ways to increase fiber in my diet. There are so many choices: nuts such as walnuts, pecans, and pistachios; sunflower, pumpkin, chia and flax seeds; root vegetables such as beets, carrots, kohlrabi, and Jerusalem artichokes; avocados; leafy greens such as spinach, dandelion greens, escarole, kale, and chard; cabbage, onions, and leeks; lentils and beans; and whole grains such as buckwheat, brown rice, millet, quinoa, steel-cut oats, and wheat berries. Many lists of high-fiber foods may be found online. Here is one example.

People often ask about potatoes. Potatoes are not the ideal form of fiber, but once cooked and cooled, they become resistant starch, a prebiotic that feeds good gut bacteria, enabling them to produce beneficial short chain fatty acids such as butyrate. Examples of resistant starch include cooked and thoroughly cooled potatoes, sweet potatoes, rice, oats, beans, and legumes.3

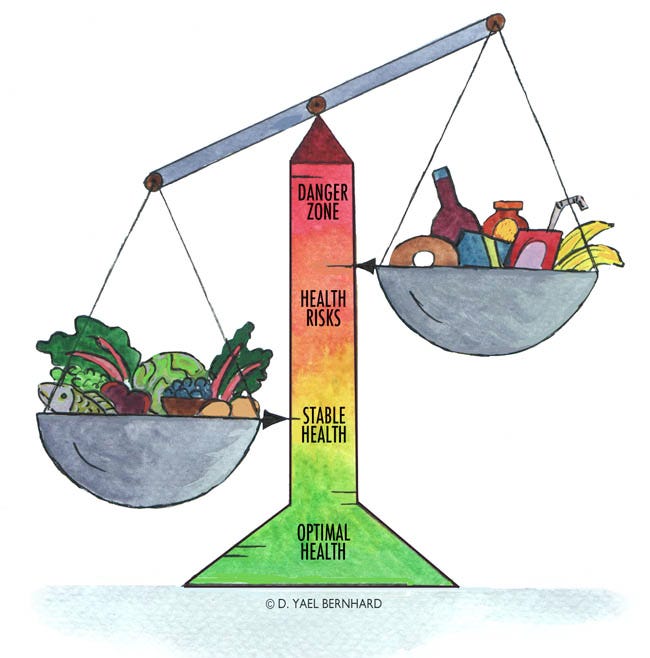

One way to think of high fiber foods is in terms of their weight. High fiber foods are often heavier and denser than their low fiber counterparts. The more fiber, the lower the risk of digestive disorders, obesity, cancer, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and cognitive decline. Eating a high fiber diet is a win-win habit to get into!

Some fibrous plants are also known as bitters. Bitters have an astringent taste, stimulating the flow of saliva and gastric juices. Bitters must be tasted in order to start the process, as receptors on the tongue trigger a physiological response.4 Bitter foods include arugula, asparagus, bitter melon, dandelion greens, endive, escarole, orange peel, rhubarb, and watercress. To find a list of bitter herbs, bitter roots, and more about bitters, see here.

‘‘Bitters promote the secretion of digestive hormones and the production of stomach acid that prepares the gut to receive a meal. They increase appetite, peristalsis, and digestive secretions in the stomach and intestines. Bitter herbs and foods have formed the bedrock of herbalism since ancient times.”5

Our bodies are designed to eat bitters, and to chew fibrous foods. Sure, if you’re traveling and have to eat on the go, it’s okay to drink a smoothie as a matter of convenience – but it’s better to eat a whole piece of fruit, or a vegetable salad. Consider making the smoothie an exception rather than the rule.

As your faithful friend, fiber is ideal to eat first at each meal, so it can regulate your digestion and keep it slow and steady, minimizing the secretion of insulin and safeguarding your insulin sensitivity. Choose low-carb fibers such as non-starchy vegetables and leafy greens. Starting your meal with a salad is the right idea. Olive oil helps you absorb the fat-soluble minerals in those vegetables. Apple cider vinegar on your salad stimulates digestive enzymes, and helps keep blood sugar down. Consider asking for olive oil and vinegar as your choice of salad dressing in a restaurant, rather than the house vinaigrette which frequently contains sugar – or worse, high fructose corn syrup. (More tips on restaurant eating in a forthcoming article.)

Can we trust nature’s design and eat in a way that cooperates with it? The best foods to befriend are those that treat you right, contributing to smooth digestion, a good gut microbiome, a happy pancreas, stable cholesterol, and a healthy metabolism.

To your good health –

Yael Bernhard

Certified Integrative Health & Nutrition Coach

Yael Bernhard is a writer, illustrator, book designer and fine art painter with a lifelong passion for nutrition and herbal medicine. She was certified by Duke University as an Integrative Health Coach in 2021 and by Cornell University in Nutrition & Healthy Living in 2022. For information about private health coaching or nutrition programs for schools, please respond directly to this newsletter, or email dyaelbernhard@protonmail.com. Visit her online gallery of illustration, fine art, and children’s books here.

Information in this newsletter is provided for educational – and inspirational – purposes only.

Are you interested in individual health coaching? Health coaching helps you reach your goals by making clear choices, taking realistic steps, and finding the resources and support you need. Respond directly to this post for more information.

Have you seen my other Substack, Image of the Week? Check it out here, and learn about my illustrations and fine art paintings, and the stories and creative process behind them.

https://www.sportskeeda.com/health-and-fitness/learning-hadza-tribe-six-secrets-healthy-long-life

https://www.sportskeeda.com/stories/living-like-the-hadza-6-secrets-to-a-healthier-life/

https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms4654#MOESM1243

Sizer & Whitney, Nutrition: Concepts & Controversies college textbook, 15th edition, 2020, pg 114.

https://www.wisewomanmentor.com/guests-4

Ibid.