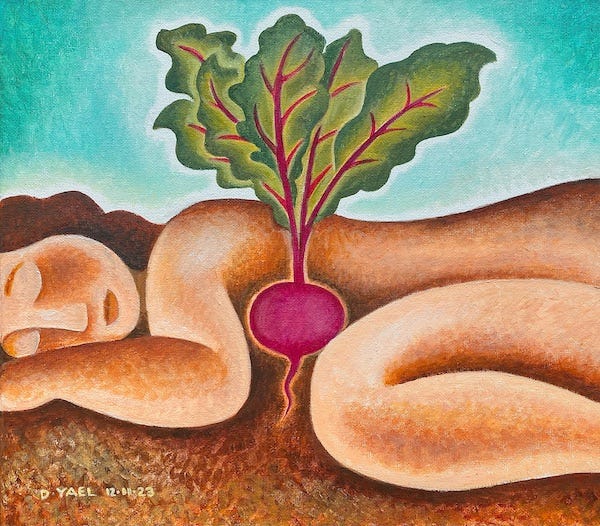

“Heart Beet”

Original illustration © 2023 Yael Bernhard

Learn more about this painting here.

Next to my bed, a huge white supplement bottle shook in the earthquake, growing to the size of a chair, its contents rattling loudly until finally the plastic burst apart, then suddenly disappeared. The earthquake subsided, and the brown rug in my bedroom became the forest floor. In the peaceful silence that followed, several stately pine trees emerged from the mist, bathed in transparent sunlight.

The dream quickly subsided as I opened my eyes to the grey light of dawn. My bedroom was in its usual messy state, but my mind was clear. I knew where this dream came from: before going to sleep, I had been writing a post for my other newsletter, Image of the Week, about children communing with trees. Drawing on my actual experience of waking up to an early morning earthquake many years ago, my unconscious was reminding me to write about trees for this newsletter, too – about connecting to the forest not only as a source of wonder and solace as children do, but also as vital nourishment.

I got up, grabbed a basket and a pair of scissors, and headed outside. Shuffling through colorful autumn leaves, I found a young white pine on the edge of my property, and snipped the soft needles into the basket, inhaling the sweet fragrance. Half the needles will be saved for making tea. The other half filled a glass jar, which I then filled again with apple cider vinegar (boiled first to pasteurize and cooled to room temperature). Both these preparations would yield bioavailable vitamin C through the winter.1 Knowing the forest will soon be talking to my cells through this pine tree, I labeled the jar with a smily face and placed it in my cabinet, where the vinegar would extract nutrients from the pine needles for six weeks, finding its place among other herbal vinegars of leek tops, garlic, nettles, violet leaves, chickweed, and horsetail.

On the shelf above that sat bottles of supplements, including Ester-C, 500 mg per bullet-shaped pill. These had sat untouched for many months, as I had slowly come to trust food and herbal preparations to supply my body with the vitamin C it needs. I sighed, and considered throwing them out – were they worthless?

No – they were a last resort, worth keeping for isolated occasions, such as travel – so I figured, trying to justify the fact that I had spent hard-earned money on this manufactured product.

Yet most people use supplements as a first resort, with no awareness of where they come from or how they’re made. Despite widespread fraud in the supplement industry, we blindly trust these products, and assume our bodies can absorb them. Many supplements are added to processed foods– so common in our culture, we barely notice them. They fight for our attention on our screens, on billboards, on packaging itself that shouts in bright colors and bold claims.

As the Baby Boomer generation ages, few people are left alive who know any other way. Raised on a diet of consumerism and convenience, we forget that our grandparents and great-grandparents didn’t have supplements or packaged food. Unaware that the average life expectancy in our culture has actually been declining in recent decades due to the precipitous rise of chronic disease, we assume we’re better off than our ancestors were. After all, we no longer die from the acute infectious diseases that snatched babies from the cradle, or doomed soldiers to die from gangrene. Until the mid-20th century we didn’t even know about half the vitamins that are necessary for human health – aren’t we lucky to have them at our fingertips, packaged in convenient tablets and capsules and inserted into fortified foods?

Working in a health food store years ago, I remember unpacking a case of boxed cereal that proudly announced it was “fortified” with omega-3 essential fatty acids in the form of flaxseed. Knowing that ground flax quickly turns rancid, and that EFAs in general are destroyed by the high heat necessary to make crunchy flakes – and may even become harmful – I wrote to the manufacturer and inquired about the basis of this claim. The reply from the public relations department was swift: yes, the company was aware that omega-3s are destroyed by high heat, but since no scientific studies had been done to disprove their claim, they were free to print it on the box.

I was stunned. Clearly, despite its branding as a maker of “health foods,” this company had no qualms about misleading the public.

And mislead they do. A food may be listed as an ingredient even if it has been decimated, isolated, oxidized, defractionated, reduced, or otherwise manipulated into a food-like substance that is totally disconnected from nature. An example of one such torturous transformation is extrusion, the process by which a food is transformed into a malleable paste that may be used as raw material much like plastic. Along the way, the cellular matrix of the food is broken, changing its biochemical composition and nutritional profile. Check out this journey of two corn kernels in the illustration shown here, in which we see this process clearly.2 The kernel on the right is ten steps removed from its original state as it is cooked, soaked, pulverized, flattened, cut, baked, fried, colored, coated, artificially flavor-enhanced – and finally becomes a corn chip. This is not the baked cornmeal that we imagine, as the product on the shelf suggests – it’s extruded by industrial machines that run automatically, creating thousands of chips per hour, which are then packaged by other machines. These chips are made with dangerously high heat that oxidizes oils that are low quality to begin with; and it may be contaminated with carcinogenic chemicals such as glyphosate, used to grow the corn (see my article Know Your Oils for more information).

This is the meaning of ultra-processed food. The final product, a plastic bag inflated with air so as to appear fuller, may say the food-like substance inside offers “whole grain goodness” – but there is nothing whole about it, and it no longer resembles a grain. “Good” is debatable, as clearly the seller derives benefit – but as demonstrated in the illustration, this ultra-processed food offers little or no nutritional value. On the contrary, it is full of inflammatory compounds that are detrimental to human health; and empty calories that will not satiate the appetite.

What this bag of chips does offer is convenience – at a price. Not the dollar price on the bag, but the price of loss of connection to nature as a primary source of food. We do not need to set foot in the forest, or even on the earth, in order to shop for mass-produced groceries. Yet every environment is naturally endowed with a full complement of plants and trees that offer up wild food and herbs; and many towns and cities have farmers’ markets and farm stands where locally grown produce may be purchased in its whole, original form, or bought in shares from a CSA. Can we take a few steps closer to nature’s bounty?

What exactly does the term “processed food” mean? The processes that different foods undergo are quite varied, ranging from grinding spices by hand in a mortar and pestle in order to change its texture, to producing a machine-made product that could never be made at home. The former is minimally processed as a way of cooking, preparing, and preserving homemade food. The latter is ultra-processed, transforming the food to the point where it is no longer recognizable. We cannot know if these chips are colored with powdered cheese (the mere concept of which is alarming) or other substances that may be applied along a conveyor belt. We cannot see the food being made at all, as ultra-processing is carefully shielded from consumers’ eyes. Imagine going to dinner at a friend’s house and being forbidden to enter or view the kitchen. Imagine, conversely, if food packaging showed unadorned photos of where and how the contents are actually grown and produced.

For millions of American children, 60% of their diet is comprised of ultra-processed food, resulting in not just nutritional deficiencies and increasing rates of chronic disease, but also what is now known as “nature deficit disorder.” I remember the first time my parents took me apple-picking as a child. I was amazed to see a real apple dangling from a tree – a living, growing orb, ripened in the sun, perfectly flawed. I knew this is where apples come from, but I had never seen it before, and never thought about it. As my father lifted me up to reach the fruit, I smelled the earthy scent of the leaves beneath our feet, and something primal was sparked – perhaps my very first connection to nature. That’s the memory that partly inspired me to write and illustrate my children’s book, Just Like Me, Climbing A Tree (Wisdom Tales Press, 2015), featured in the above-mentioned post.

Illustration from “Just Like Me, Climbing A Tree”

How far is your food removed from its source? Pull up a beet from your own garden, and you’ve got its soil – and living microbes – on your fingers, becoming part of your microbiome through your skin. Pick an apple yourself, and you’ve touched the apple’s tree, felt its roots under your feet, maybe watched the tree grow through changing seasons. You have a relationship with that tree and the fruit it bears. Chop the apple and cook it into apple sauce, and it’s one step removed – minimally processed by hand, at home. Buy apple cider from a local farm stand, and now it’s two steps removed from its source. You’ve never seen the tree, or held the apple. Buy apple juice in printed cartons, and you have no connection to the apple at all – no idea where it came from, what kind of apple it was, what was sprayed on it (even if it’s organic), who handled it, what machines pressed it, and how its packaging is affecting its nutrients. This is processed apple juice. Eat apple pie in a diner, and you’re probably eating something made with processed ingredients, such as artificial shortening in the crust. Eat an apple donut from a fast food joint, and you’ve eaten an ultra-processed food-like substance that’s about as connected to an apple as a satellite is to the earth. The shiny foil, plastic containers, labeled glass, or glossy cardboard in which these foods are packaged only add to the disconnection, polluting our bodies and minds as well as the environment.

Words such as “natural,” “organic,” “processed” and “ultra-processed” simply do not cover the full array of foods available to us today. These blunt terms do not allow for the many gradations in between. A more nuanced understanding enables more conscious choices. There are whole foods in their original form; foods minimally processed and prepared at home; moderately-processed foods that are still fairly wholesome; commercial foods that are relatively non-toxic; mass-manufactured packaged foods; and ultra-processed foods with fake, chemical ingredients that bear almost no resemblance at all to real food. Moving along this spectrum, we might think of a peach; a homemade peach pie; peach jam sold at a farmers’ market; peach fruit leather sold in a health food store; canned sliced peaches in sweetened and preserved syrup; and peach pop tarts.

Processed food has tricked us into thinking of food preparation as too onerous for our busy lifestyles. But if you take a few steps closer to food in its original form, healthy eating becomes simpler. Slice an apple and dip it in tahini, rather than taking on the project of baking an apple crisp. Wash a pear and grab some plain almonds to take on an outing, rather than buying a granola bar with 26 ingredients, or mixed nuts roasted in unhealthy oils and sold in a plastic jug. Roll a slice of turkey in a romaine lettuce leaf with a squeeze of mustard, rather than buying a pre-made sandwich wrapped in plastic. Returning to this simplicity is what wins back the time we think we save when we buy convenient products.

Food is information – not just nutrition facts on a label, but cellular information, signaling your body to function on a microscopic level. If you don’t understand the ingredients on a food label, your cells may not properly comprehend them, either. A good general guideline is to stick with simple foods with five ingredients or less – or better yet, no ingredients or label at all. Chestnut flour crackers with a texture like packing material may be gluten-free and organic, but they bear no resemblance to chestnuts. Try a handful of hazelnuts instead; or sugar snap peas, crunchy and sweet; or sliced kohlrabi with your favorite cheese. Even imported fruits like pomegranates and kiwis are generally less expensive than packaged snacks. Many make easy take-along treats. Why not eat a whole, plain cucumber? It is, after all, a fruit.

Take one step closer to nature, and you might find some wild food to harvest, too, rich in micronutrients and hardy from exposure to the elements: a wild watercress patch along a road; wild chickweed in your flower beds; a patch of stinging nettles to be added to soup or dried for a nourishing infusion; a cluster of fragrant wild mint; wild leeks in springtime; wild oyster mushrooms growing from a fallen log; wild rosemary in many parts of the world; wild chanterelles under a conifer tree; or wild spinach (lamb’s quarters), a very common weed. Dandelion greens are everywhere, rich in carotenes, vitamin C, potassium, calcium, iron, B vitamins, and protein;3 and wild blackberries may be found on the edge of parking lots and on many an ordinary walk, offering a burst of natural sweetness with vitamin C and vitamin K along the way.

There’s a hidden ingredient in these foods that you won’t find on any label: it’s love. Not romantic love – words like agape, ardor, and affection come to mind. Affection for fruits as they grow from the swollen base of a pollinated flower, or for tender green seedlings that emerge from the soil, pushing upward toward the sun bursting with phytonutrients. Ardor for living creatures in all colors and shapes, vibrant, fresh and alive. I love the ruby-red orb of a beet like I love the perfect mandala of a dahlia, the tiny fringes of a hedgehog mushroom, the graceful flight of a great blue heron. Nature’s works of art are exquisite gifts of beauty and nourishment, inspiring agape for our intertwinement with the web of life.

Can you feel ardor for the foods you buy while shopping? Think of the life lived by a wild salmon, the vigor and sunlight and smaller prey that make it so vibrant and pink. When you lift it from the pan, can you taste that in your mouth? After you chew and swallow, taking in the flesh of the fish – can you feel it becoming part of your cells? Can you trust food to provide your body with the nutrients it needs?

Nutrition habits exist along a spectrum, and your position along that line is constantly changing – nor is it always a straight line. You’re free to move, and to follow the curves of your own unique path. The point is to keep moving in the right direction, toward wholeness and health. One step at a time, you can fall in love with your food and reconnect to its original nature. All you need is a basket and a pair of scissors.

To your good health –

Yael Bernhard

Certified Integrative Health & Nutrition Coach

Yael Bernhard is a writer, illustrator, book designer and fine art painter with a lifelong passion for nutrition and herbal medicine. She was certified by Duke University as an Integrative Health Coach in 2021 and by Cornell University in Nutrition & Healthy Living in 2022. For information about private health coaching or nutrition programs for schools, please respond directly to this newsletter, or email dyaelbernhard@protonmail.com. Her art newsletter, “Image of the Week,” may be found here. Visit her online gallery of illustration, fine art, and children’s books here.

Information in this newsletter is provided for educational – and inspirational – purposes only.

http://www.susunweed.com/Article_Pine-Keeps-You-Fine.htm

https://theherbalacademy.com/8-ways-use-pine-needles/

If you can’t see the illustration, originally published in the Washington Post, please respond directly to this article, and I will send it to you.

http://www.susunweed.com/herbal_ezine/May10/grandmother.htm

http://www.susunweed.com/Article_Wild_Food1.htm